Energy | A relevant, binding constraint

REVIEW: Triggernometry interview: ‘Climate Activism is Religion’

- Date

-

Richard Lyon

Richard Lyon

Triggernometry is a YouTube show and podcast run by comedians Konstantin Kisin and Francis Foster. In their most recent interview, “Climate Activism is a Religion”, editor of HumanProgress.org Marian Tupy offers a perfect illustration of the fundamental defects that cripple conventional economic reasoning about energy. It’s well worth watching. In this extended essay, we’ll look at those defects, where they come from, and why they matters.

Marian is a well informed and engaging speaker, and there is much with which to agree in the interview. Many of the issues we face now are the consequence of the failure of an irrational energy policy, rather than the consequence of the matters that energy policy (in its present form) concerns itself with. The root cause of irrationality in energy policy is the contamination of climate science by ideological, political, and commercial moral hazard, the abandonment of the scientific method, and the elevation of the climate to a religion in the minds of its extremist advocates. The failures of irrational energy policy are bringing about the collapse of our financial system and society and, with them, the risk of civil unrest and the rise of “nasty” parties to replace those of the current Left and Right.

Although Marian identifies and explains the problem very well, when he turns to solutions, the theoretical grounds he sets out for rejecting it are almost as flawed as the policy he criticises. Having correctly observed that solutions to the problem lie in high density sources of energy, such as gas and nuclear, he claims that the most prominent of those – oil – is not running out, and that we have “hundreds” of years of remaining supply. The amount of resource available to us is, in fact, an irrelevant, non-binding constraint on our ability to create economic value. That’s because, as humans, we have a limitless ability to innovate: technology, we learn, is ‘dynamic’; if we need something, its price will rise and we’ll either find more of it, use less of it, or substitute it with something else entirely. As evidence of this, he notes, life is better than it was 100 years ago and, as the population of the planet increases, the price of everything is falling.

Marian’s institution, HumanProgress.org, is parented by The Cato Institute, an American libertarian think tank. It also receives significant support from The John Templeton Foundation. Both advance an extreme form of capitalism 1 in which free markets play a central role in optimising the allocation of scarce resources. The intellectual framework for this ideology is neoclassical economics, also sometimes called ‘neoliberal’ or ‘Washington Consensus’ economics.

Neoclassical economics is the product of the largely unsuccessful attempt to elevate economics from a “social science” into an actual science. It arose from the struggle to reject concerns that emerged after the Second World War about the ability of the Earth’s finite resource base to accommodate indefinite exponential growth. 2

Neoclassical economic’s theoretical shortcomings are well understood. This rather pithy extract gives a flavour: 3

The realization that the conceptual base for much of [neoclassical] economics is quite flimsy is no longer news to either those who follow events within the field or to many interested outsiders in the natural sciences…Some twenty years ago in the journal Science, Nobel prize winner in economics Wassily Leontief found the basic models of economics “unable to advance in any perceptible way a systematic understanding of the operation of a real economic system.” Instead they were based on “sets of more or less plausible but entirely arbitrary assumptions” leading to “precisely stated but irrelevant theoretical conclusions…[Neoclassical economic models] are also enormously and deeply flawed, in a way and to a degree that is almost inconceivable and even an embarrassment to someone who has a background in natural sciences or who believes in generating truth from the use of the scientific method.

The central failure of neoclassical economic theory about resources lies in its failure to recognise the significance of exponential growth in economic and financial systems.

The blindspot: exponential growth

Exponential growth arises whenever you want something that is proportional to what you already have. You want a 5% pay rise, not the £5 pay rise that your grandfather would have considered generous.

We extract resources at a rate that rises exponentially.

Exponential systems have strange, unintuitive properties. In linear systems, quantities increase by a fixed amount in equal time periods – 1, 2, 3, 4, etc. In exponential systems, quantities double in equal time periods – 1, 2, 4, 8, etc. In exponential systems, nothing happens for a long time, then everything happens. It’s a simple proof, available to a 7th grade student, that the time to exhaust a finite stock that is drawn down at a rate that rises exponentially is essentially independent of the estimated volume of stock originally in place, and that you get almost no warning that it’s about to exhaust. 4

Neoclassical economics in general, and Marian in particular, are oblivious to those strange properties. This oblivion is responsible for many of their startling claims about the real world, such as Marian’s claim that the number of atoms in the world is an irrelevant and non-binding constraint on human ability to create economic value.

Turning now to those claims…

Oil is running out

Marian believes that oil is not running out and that, if we wanted to, we could search other parts of the world for it. That’s because he’s unaware of the history of oil discovery, the recent effect on oil production of printing vast quantities of fake money, and basic petroleum geology.

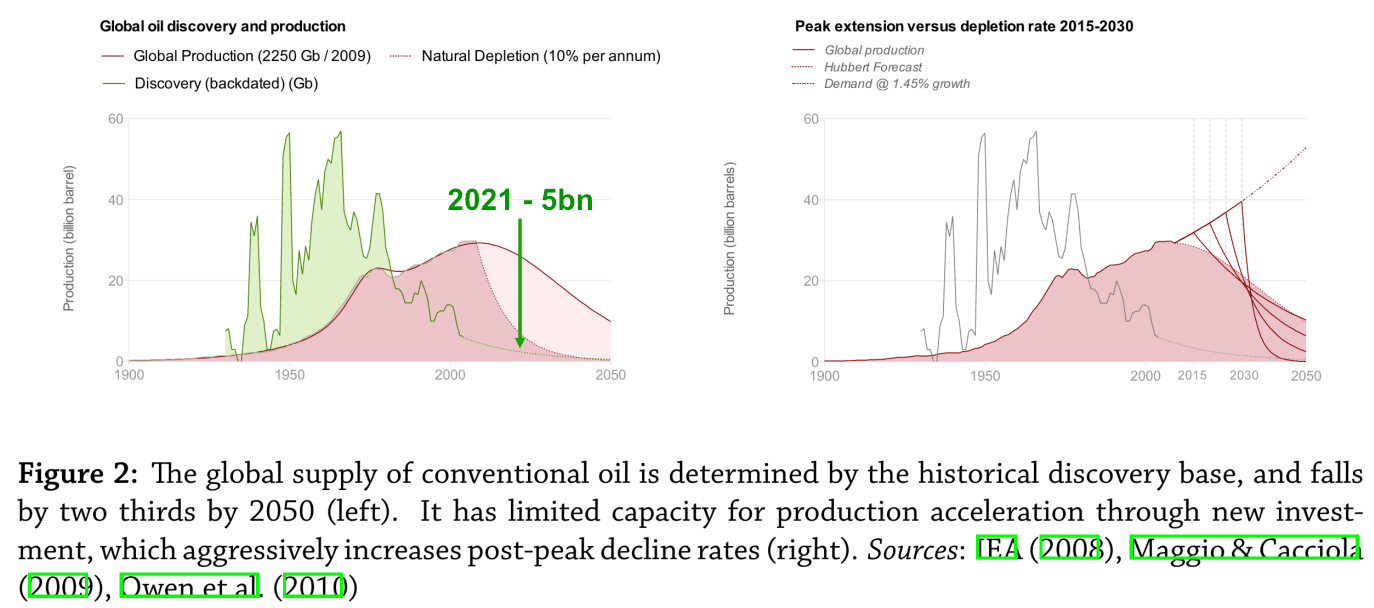

We can’t produce what we haven’t discovered. So the volume of oil that can be produced – a volume that Marian supposes is arbitrary – is in fact defined by the volume of oil that has, and can reasonably expected to be, discovered. Discovery of affordable oil (left hand panel, below) peaked around the date of the moon landing in 1969 and has declined at around 5% per year ever since. That establishes the maximum volume of affordable oil that will ever be discovered, and therefore produced. It’s about 2 trillion barrels.

Figure 1. The rate of discovery of affordable oil has collapsed - discovery in 2021 was 5 billion barrels. Source: Lyon, Richard. 2010. ‘The Optimism Index: Quantifying the Uncertainty of Energy Policy’.

We produce that discovered and discoverable volume on an easy first/difficult last basis. Ordinarily, that produces a peak in output corresponding to the moment that the decline rate of all the existing easy production exceeds the rate at which we can economically add successively harder new production. The peak was around 2008. Since 2008, we’ve been printing literally unimaginable quantities of fake money. That fake money has in part been funding the production of uneconomic oil, delaying the onset of peak production (right hand panel, above). It is this delay in the onset of peak production that has produced Marian’s perception of an infinite acting pool of oil.

We don’t look for oil in parts of the world that it has not previously been found for the same reason that we don’t look for kangaroos in parts of world where they have not previously been found. Just as understanding the origins of kangaroos tells us where (and where not) to look for kangaroos, understanding the origins of oil (ironically, in two periods of abundant life associated with previous global warming periods) tells us where and where not to look for oil. And we’ve already looked in all those places.

Resources are a binding constraint

Marian is untroubled by any of this because, in neoclassical economic theory, human economic activity is limited not by the number of atoms on the planet, but by the cost of those atoms. As scarcity arises, cost rises. As cost rises, incentives to find alternatives rise, those incentives yield new discoveries, and costs lower. The engine of this is human ingenuity, expressed through technology.

Marian is unaware of the defining – and crippling – effect that energy scarcity has on our ability to response to resource scarcity, and the circular argument embedded in his faith in the ability of technology to solve energy scarcity.

The illusion of permanent growth – affordable vs. unaffordable energy

Rising resource scarcity causes the cost of the resource to rise. With functioning economic and financial systems to provide the operations necessary to relieve scarcity, that increase can be responded to. But, although energy is a resource, rising energy scarcity is not like rising resource scarcity because all economic activity – including the production of energy – requires energy. So when the cost of energy goes up, the cost of everything goes up. Above a certain energy cost – for oil, about $90 a barrel – the economy can no longer function, and energy scarcity cannot be relieved.

We saw this in 2008. In 2005, production of “affordable oil” breached the limit of the capacity of the global system to deliver it. That drove the oil price up, reaching $140 per barrel in June 2008 and triggering the ongoing crisis of a stagnated economy.

Stagnation or contraction of the economic system in turn forces contraction of the financial system. 5 Why? Because money is produced from goods and services, which require energy. Energy expansion means more goods, more services, and more money. Energy contraction means fewer goods, fewer services, and less money. When energy contracts, money has to be withdrawn – we must become poorer – to preserve the value of what money can be supported by the new level of energy, goods, and services.

Again, we saw this in 2008. Instead of managing the contraction of the financial system necessitated by the contraction of the energy system by withdrawing money, we responded by printing unimaginable quantities of irredeemable debt – fake money – to try and fill the widening gap. That is now driving hyperinflation and visibly destabilising the financial system.

Taken together, these economic and financial limits establish the two fundamental categories of energy that exist in the world: “affordable” energy i.e. the types that allow economies and financial systems to function, thereby relieving resource scarcities; and “unaffordable” energy i.e. the types that cause economies and financial systems to collapse. Most so-called “unconventional” types of oil (tar sands, bio fuels, oils from fracturing, etc.) and so-called “renewable” energies (solar, wind, biofuels, etc.) are “unaffordable” in this sense.

And that is the first reason why Marian’s claim that when the price doubles, the incentive to look for more oil doubles, and therefore the amount of oil doubles, is absurd.

Let’s look at the second.

The illusion of technology – the dependence on energy

As you can see from Fig. 1 above, contrary to Marian’s claims about technology, it hasn’t actually increased the volume of discoverable, affordable oil. Since the peak of discovery of affordable oil in 1969, we’ve invented all sorts of disruptive technologies that should have revolutionised the discovery of affordable oil: the miniaturisation of electronics and the ability to send sensors down hostile well bores; the ability to visualise and model the subsurface with supercomputers; the ability to acquire geophysical data over the whole surface of the earth from low earth orbit; the development of novel materials, etc. And it’s made barely noticeable difference to the discovery decline rate. Replacement volumes in 2021 were the lowest in 80 years, and oil companies now have around 15 years of oil volumes left. 6

But that’s not the core problem with Marian’s theory.

It’s repeated to the point of platitude: “Humans can solve any problem”. That statement misses the essential qualification: “Given a sufficient amount of excess energy, humans can solve any problem”. As if to illustrate his claim, Marin quotes neoclassical economist Thomas Sowell: 7

The cavemen had the same natural resources at their disposal as we have today, and the difference between their standard of living and ours is a difference between the knowledge they could bring to bear on those resources and the knowledge used today.

Well, no. What the cavemen had at their disposal, and the difference between their standard of living and ours now, was the possibility of 10,000 years of energy transitions to successively more dense fuel types (wood -> charcoal -> coal -> oil/gas -> nuclear) and, at each stage, large quantities of the fuel currently in use with which to build out the next, higher density energy system.

We’ve got so used to this arrangement that we’re unaware of it, much as fish are presumably unaware of the water they are born and die in. It’s the confounding factor he’s overlooked when concluding that it is technology, not rising energy density, that has led to life getting better, and costs falling.

And that lack awareness of the condition upon which energy transitions depend is what lured neoclassical economic resource theory into committing the circular fallacy that an economy that has exhausted stocks of affordable, high net energy fuels can solve the problem of transitioning to one based on incredibly low net energy fuels.

Our energy resources are already fully allocated to sustaining the operations that support current living arrangements – which include, for example, feeding some fraction of the 5 billion additional humans that are now alive since the start of the hydrocarbon era. Even these are inadequate – as net energy contracts, we also now have to print trillions of dollars on an ongoing basis to sustain the illusion that our economic and financial systems are currently viable.

Which of those energy intensive operations would Marian switch off to support his technology projects? Industrial agriculture? Water and waste systems? Medicines and health care? The internet?

He’s not clear.

What this reveals: the state of energy literacy

It’s an understatement to say that energy is important. Our lives – literally – depend on it. We don’t think about it for the same reason that fish don’t think about water. But you can bet fish think about water when the pond dries out. And our energy pond is drying out fast.

Throughout the interview, hosts Konstantin and Francis note how reassuring they find Marian’s account of our energy supply problem. Which is exactly the purpose for which neoclassical economic theory was invented. The theory that Nobel prize winning economists note is “unable to advance in any perceptible way a systematic understanding of the operation of a real economic system”.

We should know the relationship between energy and real economic and finance systems, the effects that changes in the energy system produce in real economic and finance systems, and the limitations that real economic and finance systems place on our ability to secure energy.

We should be capable of basic reasoning processes, for example that something that depends on something else for producing things can’t produce the thing that it depends on.

We should know the difference, thermodynamically, between a gas fired power station and a summer breeze. And we should understand intuitively why adding up lots and lots of wind turbines no more reproduces a gas fired power station than adding up lots and lots of ski lift queues reproduces a ‘black’ ski run.

Energy should be taught in schools, alongside reading, writing, and arithmetic.

In other words: we need energy literacy. Fast.

-

The political views that HumanProgress.org advocates for are not relevant to the scope of this essay. ↩︎

-

This is quite separate from recent, hypothesised concerns about the effect of CO2 emissions on the Earth’s climate arising from economic activity that form the basis of climate extremism. ↩︎

-

See: Hall, Charles A S, and Kent A Klitgaard. 2006. ‘The Need For A New, Biophysical-Based Paradigm In Economics For The Second Half Of The Age Of Oil’ 1 (1): 19. ↩︎

-

A thought experiment might help. Imagine that you are tied to a seat on the top row of Wembley Stadium, and that I am standing on the centre line with a magic drop of water that doubles in volume every minute: when will you drown? The answer is, “in around 40 minutes”. If Wembley Stadium has twice the volume that I’ve estimated, then you’ll get an extra minute. And if you get worried about this arrangement when Wembley is, say, quarter full then, having sat complacently for nearly 40 minutes, you’ll have two minutes to call the police. The volume of breathable air in Wembley Stadium, it turns out, is a very relevant and binding constraint, and our intuition about exponential processes – such as the rate at which we consume resources – is highly unreliable. ↩︎

-

Simple stagnation is sufficient to produce this effect. The financial system, as we have constructed it, employs interest to price and reward risk. So the quantity of debt rises exponentially over time. Therefore, to maintain the relationship between the units of debt and productive assets in the economy, the economy has to grow exponentially. Stagnation of economic growth establishes an exponentially rising gap between the financial and economic systems, eventually destabilising the financial system. ↩︎

-

‘Rystad Energy - Big Oil Could See Proven Reserves Run out in Less than 15 Years as Output Is Not Replaced by Discoveries’. 2021. 11 May 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20210511193735/https://www.rystadenergy.com/newsevents/news/press-releases/big-oil-could-see-proven-reserves-run-out-in-less-than-15-years-as-output-is-not-replaced-by-discoveries/. ↩︎

-

Thomas Sowell. 1996. Knowledge And Decisions. p.47 Basic Books. ↩︎