Energy | When there's not enough

Net Energy

- Date

-

Richard Lyon

Richard Lyon

The absurdity of ongoing attempts to replace ultra dense hydrocarbon with ultra diffuse, so-called “renewable” energy devices, is evident from the fundamental governing equation:

Net energy = (EROEI - 1) / EROEI

It establishes an unintuitive property shared by many physical systems: “Nothing happens for a long time, then everything happens all at once”.

That unintuitive behaviour has scrambled our reasoning about energy. It’s why the true energy and financial costs of attempts to replace hydrocarbon with sunbeams and summer breezes haven’t even begun to be estimated.

Here’s why.

First, some basics. It takes energy to get energy. From every, say, hundred units of energy at our disposal, some fraction must be reserved to procure the next hundred. We feed and heat ourselves with whatever is left over.

A miraculous property of hydrocarbon is that twenty or thirty units of new energy can be obtained for each reserved unit. A disastrous property of ‘renewables’ is that, even without accounting for vast hydrocarbon energy subsidies omitted from current life-cycle estimates, a reserved unit provides only single-digit units of new energy.

Fans of renewables rejoice when studies appear to show that their gadgets can power their own manufacturing processes with a bit left over for us. They forget that the purpose of an energy system is not to power its own manufacturing system. Its purpose is to power our lives.

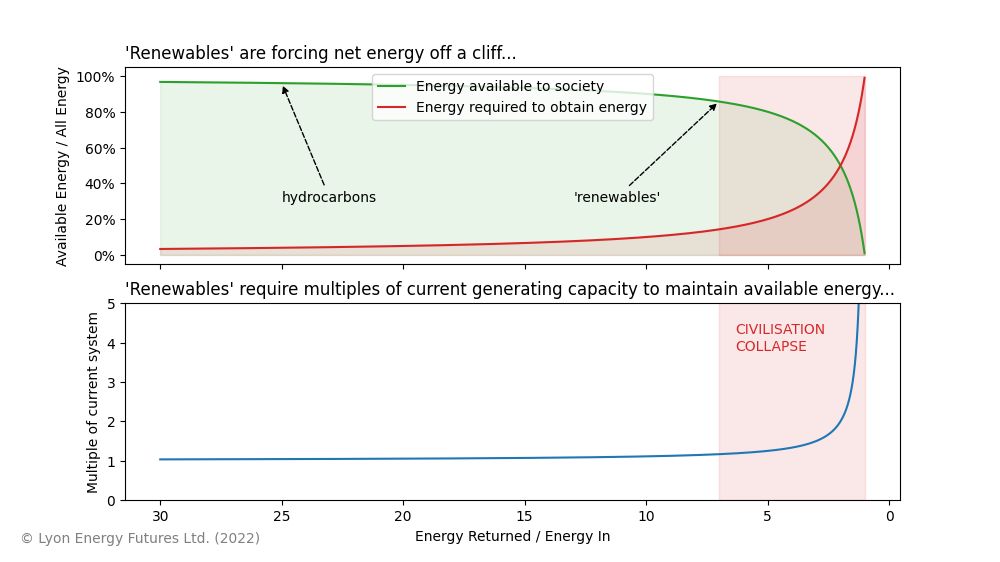

To see why this matters, look at the illustration. Along the horizontal axis, I’ve plotted the ratio of usable energy to all energy invested to obtain it (called the “Energy Return on Energy Invested”, or EROEI).

Net energy

In the top chart, I’ve converted EROEI into the percentages of the total energy spent on obtaining new energy, and on keeping ourselves alive, as energy sources deteriorate.

It reveals renewables’ exponential “ground rush” effect.

Hydrocarbon average EROI has fallen over time from 100+ to 20+ today. It’s made almost no difference to the net energy available to us to live on.

Most renewable EROIEs, though, are in single digits. As the crisis they produce in the energy system deepens, the hydrocarbon energy inputs that their lifecycle energy studies overlook, and the vast energy costs of provisioning the thermal standby and energy storage facilities necessary to adapt their intermittency to industrial civilisation, are coming rapidly into view. That drags their true EROEI down further.

Unlike hydrocarbon, each renewables EROEI point reduction costs tens of percentage points of net energy. No civilisation has ever survived that rate of energy withdrawal.

It’s worse. At 50% of today’s net energy, we’d need twice current global generating capacity to maintain the energy we live on. The lower chart shows how many multiples of the world’s current generating capacity we’d require to maintain living arrangements as ‘renewables’ drag EROEI down.